The definitive diagnosis is made using CT aortography. On suspicion of this diagnosis, the patient should be treated as a medical emergency with immediate referral and transport to hospital by an appropriate prehospital provider. Physical examination may be entirely normal or reveal hypertension, neurological deficits, peripheral ischaemia, blood pressure or pulse differentials between right and left sides, and new murmurs/muffled heart sounds/pericardial friction rub/jugular venous distension.

The pain is typically sudden-onset and described as a tearing or ripping pain radiating through to the inter-scapular area and associated with dyspnoea, syncope, neurological symptoms or abdominal pain. Risk factors for aortic dissection include smoking and cocaine use, connective tissue disorders, infection and inflammation, atherosclerosis, previous heart or aortic valve surgery, bicuspid aortic valves, blunt trauma and pregnancy. 3 Definitive diagnosis is made with computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) in most cases. A negative D-dimer using quantitative enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) effectively excludes PE in patients with low pretest probability. Decision rules such as the Wells score or pulmonary embolism rule-out criteria (PERC) assist in determining the probability of pulmonary embolus and guide the use of D-dimer testing and clinical management. The electrocardiogram (ECG) may be normal or show non-specific changes including, tachycardia, S1Q3T3 (S wave in lead I, Q wave and T wave inversion in lead III), incomplete/complete right bundle branch block, right axis deviation, inverted T-wave (V2–3), peaked P waves and atrial flutter. Generally, patients complain of a sharp pleuritic pain, and may be short of breath or have haemoptysis, tachycardia and hypoxemia. Pulmonary embolism (PE) risk factors include the presence or clinical suspicion of deep vein thrombosis (DVT), past history of DVT/PE, active malignancy, recent trauma, surgery or immobility, and use of exogenous oestrogen. The approach to patients with possible cardiac chest pain. *This differential diagnosis is not intended to be exhaustiveĪdapted with permission from the Medical Journal of Australia, from Parsonage WA, Cullen L and Younger JF.

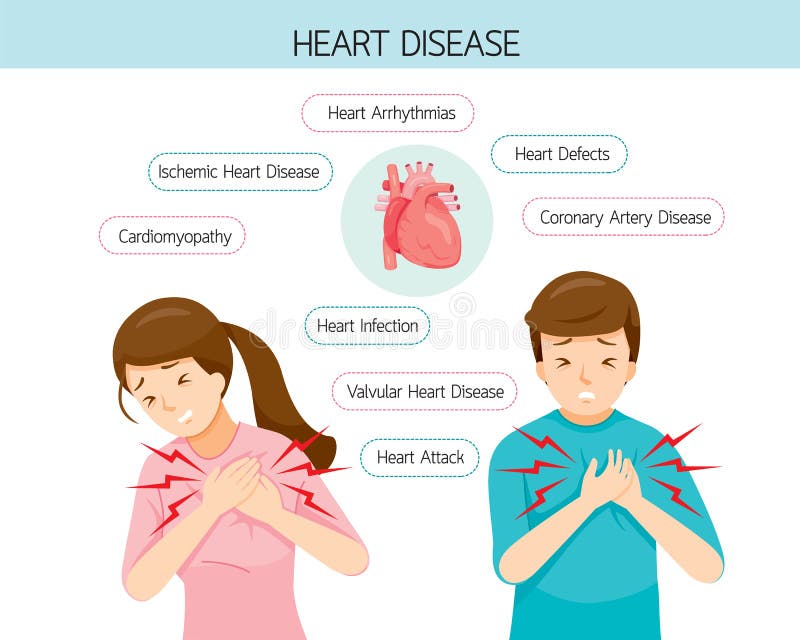

Angina pectoris due to stable coronary artery disease.Acute coronary syndrome (acute myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris)Ĭhronic conditions requiring urgent evaluation.Differential diagnosis of (non‑traumatic) chest pain* Serious conditions include ACS, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection and spontaneous pneumothorax (Box 1). Where minor conditions are confidently diagnosed, referral to the emergency department may not be necessary. Differential diagnosis of chest painĪ number of life-threatening and minor conditions may present with chest pain. Finally, hospital-based risk stratification and management will be described, providing an outline of what patients can expect from their referral to hospital. It will discuss key differentials that must be considered, and essential primary care investigations and management. 1 This article will focus on diagnosis and early management of patients with possible acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Given that some causes of chest pain are potentially lethal, the challenge is to make an accurate diagnosis. Chest pain is a common complaint of patients presenting to primary care physicians and emergency departments.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)